Andrew Monteleone PT, DPT, OCS

For many of us, our days are spent sitting in front of a computer screen. We all know that exercising is important, but many forms are repetitive and unstimulating. For these reasons and more, many people are getting into rock climbing. With its community-based environment and puzzle-like routes (called “problems”), climbing provides a workout disguised as a mentally stimulating and varying physical activity. There are many climbing gyms in Seattle offering bouldering, top rope, and lead climbing and as the climbing community continues to grow, so too does the incidence of injury.

Bouldering is the most popular form of indoor climbing as it requires no ropes and can be done without a partner. With its dynamic, gymnastic, and powerful movements, it should come as no surprise that bouldering has the highest incidence of injury of all climbing disciplines (Jones article).

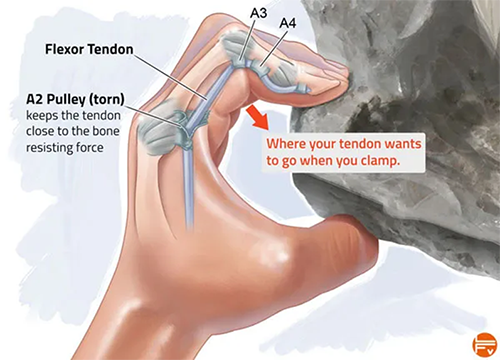

Because of the heavy demands placed on your upper body with climbing, overuse injuries occur most frequently in your upper extremities. Injuries to the hands and fingers account for more than 50% of all climbing injuries. Common finger injuries include pulley ruptures or tears, most commonly A2-A4 (see diagram below), particularly with crimps and sloper holds which can create pain, swelling, and a “bowstringing” of the flexor tendons impacting your ROM and strength with climbing (Jones article).

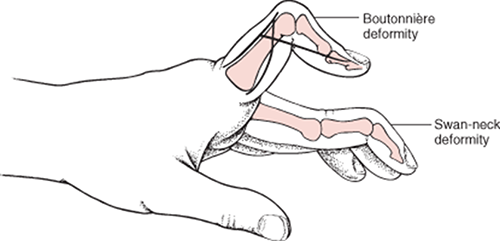

Due to the direct forces in your fingers with a full crimp position, you can also impact ligaments and joint structures in your knuckles resulting in Swann neck and Boutonniere deformities seen below.

Similarly, injuries impact the wrist (e.g. carpal tunnel syndrome or a sprain to your triangular fibrocartilage complex), elbow (flexor musculature tendinopathies), and shoulder (17% of all climbing injuries, most frequently a labral tear or subacromial impingement) (Sims article).

Whether you get your first climbing-related injury or are dealing with more chronic aches and pains, a physical therapist will likely be able to help you. They are experts in evaluating and treating musculoskeletal injuries and can provide invaluable insight into the underlying causes of the injury and appropriate rehabilitation strategies (including exercise, stretches, manual therapy, and a supervised progression to return to sport).

While climbing movements and hold types vary, as the sport relies heavily on the latissimus dorsi, pectoralis major (for compression problems), and the wrist and finger flexors, this repetitive activity can create many musculoskeletal imbalances that contribute to an increased risk for overuse injury. Consequently, it is important to incorporate a comprehensive training program to rehabilitate from an injury, reduce the risk for injury or re-injury, and ultimately improve your climbing performance. A recent study of climbers found that a comprehensive training approach (involving understanding anatomy and mechanisms for tissue injury in conjunction with a training program focusing on flexibility and strengthening reduced the risk for a minor injury by 2.3x and up to 8x for a more severe injury (Kozin article).

If any of this sounds unfamiliar, or you are unsure where to start with a preventative program, we are here to help. Come stop by and see one of our physical therapists for advice on how to accomplish all these preventative tips. We are movement experts and injury prevention specialists after all.

Rock climbing is a challenging yet rewarding sport that is engaging physically and mentally for individuals of all ages and levels. By supplementing our typical climbing routine with the appropriate flexibility, strength training, and technical work we can spend less time recovering from an injury and more time on the wall.